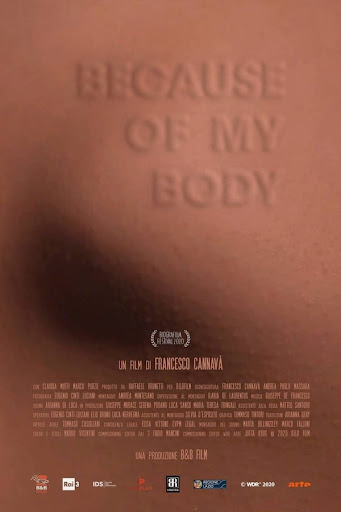

Because of My Body, film review

By Ana P. Santos

How can a disabled person experience desire and safely explore their sexuality? And how can we as a society give them a safe space to do it?

Twenty-one-year old Claudia wants to know what it feels like to be kissed and caressed. Over the summer, Claudia watched as girls her age went off on adventures with their lovers. She longs to experience what it is like to be desired.

Claudia has spina bifida, a condition that affects the spine and causes damage to the spinal cord and nerves. Claudia relies on assistance for many of her daily tasks.

Claudia signs up for an experimental program to work with a love giver or a sexual assistance for disabled people to get to know herself, both physically and emotionally. She is paired with Marco who is training to be a love giver.

Claudia’s story of exploration, questioning, and discovery are captured in Because of My Body, a film directed by Francesco Cannavà and screened at the Porn Film Festival Berlin (PFF Berlin). The film is an intimate portrait of a young woman who bares her emotions and her struggle for autonomy over her body and her identity.

Scenes filled with emotion and wonder delicately trace the contours and many layers of sexuality and disability and the tumble of emotions that come as part of this exploration.

In one scene, Claudia tells Marco how she mustered up the courage to tell a boy she liked that she wanted to have sex with him. “I don’t want to have to go all the way to your place to have sex with a disabled person,” he told her.

In another scene, Marco shows Claudia drawings of the male and female genitalia, naming each part. The scene ends with Marco gifting Claudia with a handheld mirror so she can become intimately acquainted with her body

The film is courageous not only because it sheds a light on female sexuality among disabled people, but because of the way that it does this through the character of Claudia who exposes her vulnerability, her body, and her emotions with such raw intimacy that as a viewer, made me feel like I was being let into her life.

An understudied and overlooked taboo

Sexuality among disabled persons is understudied, overlooked, and dismissed. Existing academic scholarship and research studies about sexuality and disability usually focus on men.

According to sex educator and inclusivity consultant Damien Weatherald, sex and disability is still a taboo subject that needs more research to break down common misconceptions that include disabled people not having sex.

“As someone who is disabled, this is far from the truth. I speak to many disabled people who believe that they have better sex lives because more thought has to go into it,” said Damien.

Part of the discussion that Damien would like to see around sex and disability is the acknowledgement of disabled people as sexual beings who may want to experience sexual pleasure. In addition, Damien hopes for a wider definition of what sex and pleasure can mean for disabled people.

“We need to get away from the belief that sex always means penis into vagina or penetration. This may not always be possible for some people due to different impairments, but they may find their own way of achieving sexual pleasure,” Damien explained.

Like me, Damien is a Pleasure Fellow for the Pleasure Project, a UK-based organization that has been leading the advocacy on sex-positive and pleasure-based approaches to sexual health.

The Pleasure Project drafted The Pleasure Principles, a guide for sexuality educators, advocates, and anyone interested in promoting sex-positive and pleasure-based public health programs and sexuality education.

Organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), the world’s largest service provider of reproductive and sexual health services, have endorsed The Pleasure Principles and the call for embracing pleasure as a crucial factor for improving sex education and encouraging safer sex behavior such as the correct and consistent use of condoms.

It was meeting Damien during our fellowship year and a graduate school subject called Crip Theory, which presents new ways of understanding disability, that got me to thinking about how sexuality and disability could be represented and discussed in a sex-positive way.

The Pleasure Principles call for sex-positive and rights-based approaches to sexual health and recognizes the diversity of sexual experiences and the safe and consensual pleasure we derive from these experiences as a human right. The Pleasure Principle Think Universal asserts that pleasure is for everybody and every body just as the movie About My Body puts forward.

When I told Damien about the movie, he thought that the focus on love givers was important because, as he explained it, for some disabled people the assistance of love givers may be the only way disabled people can experience sexual pleasure outside of sexual touch.

“It is a service that needs to become mainstream, but it is also important that it is shown or stated that disabled people can also have sexual relationships without having to use a sex worker,” Damien explained.

One scene showed Marco explaining sex toys to Claudia and then leaving her to explore how using them made her feel in private.

While About My Body may have ticked off a lot of checkboxes when it came to inclusivity and sensitivity, the varied reactions to the film during the Q&A after the movie, indicated the work that still needs to be done.

One viewer expressed their discomfort about Claudia and Marco’s engagement which had to end after eight sessions. Love givers are compensated for their services, and as explained in the film, so as not to be considered sex work, physical contact with patients is forbidden. Patients and love givers must cut off all ties after the eight sessions are completed. The viewer was concerned about how this left Claudia overwhelmed with emotions that could easily be conflated with love.

Lizzie, a love giver, who was in the audience shared about how she also tends “to fall into moments where she falls in love” with her clients. According to Lizzie, these shared moments and the intimacy that is so much part of her work makes it meaningful and fulfilling.

Unfortunately, no one in the audience was a disabled person so no one offered a different point of view which, as one viewer pointed out, may have been a matter of access. “We’re watching a film about disability in a theater that does not have a lift,” the viewer said.

Getting feedback from the disabled community avoids discussions, programs, and movie from becoming condescending, exclusionary or as Damien explained, becoming fetishized or sensationalized. “This is a problem that has happened many times in the past and it makes it harder for the disabled community to have these conversations,” he said.

About My Body was far from being based on fetish, fantasy or titillation. It was not perfect, but it was a sex – positive start to having more open and intimate discussions about sexuality and disability. ###

Editor’s Note: WHO estimates show that about one billion people experience some form of disability which is defined as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities”

The “social model of disability”, developed by disability rights activists in the 1970s and 80s, suggests that if societies were set up and constructed in a way that was accessible for people with disabilities, those individuals would not be restricted from full participation in the world around them. ###

Read more about The Social Model of Disability here:

https://www.thesocialcreatures.org/thecreaturetimes/the-social-model-of-disability

If you would like to read more about the developments in the study of sexuality of disabled people, check out the following resources:

Supporting Sexual Health and Intimacy in Care Facilities guidelines issued by the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority which state that care facilities have an “ethical and legal obligation to recognize, respect and support clients’ sexual lives”.

Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury, a clinical practice guideline by the United States Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine which encourages health care professionals to openly and proactively deal with the topic of sexuality.

![[FILM REVIEW] Because of My Body](https://thepleasureproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/2_cover-copy.jpg)